Adventures in Bonoboland

Martin Bendeler (Bonobo Conservation Initiative Australia, Director and Founder)

I am indebted to Australian GRASP for helping me take the first step on my incredible journey of 1000 miles up the Congo River to Bonoboland with Bonobo Conservation Initiative.

And I was fortunate to enjoy firsthand the fruits of Australian GRASP's

USD$3000 contribution to BCI's project to construct a community

education centre in Kokolopori that catalysed the enthusiasm and efforts of local

villagers to expand and embrace the centre. I saw it regularly used

as a venue for carpentry, textiles and soap-making activities and

training, as well as village and conservation management planning. Also,

it provided basic but comfortable accommodation for our little

group and for visiting local researchers from nearby

bonobo ranges. It was encouraging to see that relatively modest contributions like these go a very long way, but the villagers here are the bonobos real guardians and they are still desperately poor. These are my notes, scribbled at varying points along the journey. They were written to, in some small way, take my friends and family along with me. Anything beautiful in it is a reflection of the Congo, the bonobos and the wonderful people I met along the way, for which I extend my utmost gratitude. Anything tedious, clumsy, petty or just wrong is all me, for which I extend my most sincere apologies. Particular thanks goes to the dedicated, conscientious and sacrificing staff of Bonobo Conservation Initative and their local partners, who do so much with so little to protect the bonobos."

And I was fortunate to enjoy firsthand the fruits of Australian GRASP's

USD$3000 contribution to BCI's project to construct a community

education centre in Kokolopori that catalysed the enthusiasm and efforts of local

villagers to expand and embrace the centre. I saw it regularly used

as a venue for carpentry, textiles and soap-making activities and

training, as well as village and conservation management planning. Also,

it provided basic but comfortable accommodation for our little

group and for visiting local researchers from nearby

bonobo ranges. It was encouraging to see that relatively modest contributions like these go a very long way, but the villagers here are the bonobos real guardians and they are still desperately poor. These are my notes, scribbled at varying points along the journey. They were written to, in some small way, take my friends and family along with me. Anything beautiful in it is a reflection of the Congo, the bonobos and the wonderful people I met along the way, for which I extend my utmost gratitude. Anything tedious, clumsy, petty or just wrong is all me, for which I extend my most sincere apologies. Particular thanks goes to the dedicated, conscientious and sacrificing staff of Bonobo Conservation Initative and their local partners, who do so much with so little to protect the bonobos."

Martin Bendeler December 2005

Thu Nov 9

Our boat was waiting for us. Surely, never before has a group travelled upriver in such style. Three wide pirogues (dugout canoes) lashed together, 40 feet long, reed matting, tarp canopy, four bed frames with foam mattresses, a cooking area with hot coals, and the crowning glory- camping chairs with beer holders. New twin 85 horsepower engines should cut the journey time by a Third. But it will still be at least four days and I am grateful for the comfort. Sharing the journey with me are the foreigners- Paul, Arne, Michael and myself- and the Congolese- Bienvenu (aka Bienco) the BCI logistician, Augustin the Kokolopori chief and his granddaughter, Violette, Nina the cook, Charles the Best Boatman on the Congo (aka Le Blanc due to his striking green eyes), and his humble helper, Meda.

Bonobo (Photo- Arne Schiotz)

Two of the canoes contain the beds, covered by a tarp over timber, stick and vine frame. The third boat is largely uncovered, except at night and during storms, when the tarp is pulled over it, and contains the cooking equipment and the Kokolopori hitchhikers.

How do you describe such a river? A trillion litres flowing beneath. In its reflections, a monochrome extension of the grey morning sky, of the sabled green shadows of the dipping forest, of the deepest pitch blue of night's last dark and dawn's first spark, silhouette framed. Where the outboard motor churns, the water looks like a frothy Guinness/ice tea milkshake. The wet season has flooded the banks up to the lower canopy and we pass along a valley of sheer echoing cliffwalls of trees .

We are not floating on a river, we are floating on a forest. Sometimes it seems like if the water level was 20 feet higher, we could look out over the entire Congo Basin , which would have to be renamed the Congo Sea .

The river is by no means ours alone. Pirogues drift downstream, always downstream. Perhaps they sell them at their destination and walk home rather than paddle. Some are small and carry nothing but a small boy and a wicker fish trap. Others are floating huts, taking months to reach town to trade forest goods for city. Sometimes a long boat will have four or five people paddling. Most are too tired to wave but some will signal to us, sometimes to sell a fish, but usually a begging gesture that a bonobo would readily recognise. And the largest will be almost a whole village lashed together to a barge on the week long journey to Kinshasa- goats, rice sacks, families. Like Costner’s Waterworld.

Bonobo (Photo- Arne Schiotz)

Bonobo (Photo- Arne Schiotz)In wide flat clearings, thatch huts are built on stilts in the shade of palms. Little children run around in various combinations of rags, underpants and nudity along with the free-range piglets. They wave and smile and beg and throw backflips into the river. Men sleep under shaded paillotes. Women work. Great clumps of South American water weed, of the sort that has carpeted Lake Victoria, also drift by us, some in purple bloom. These clog up the space between the lashed pirogues, skimming river foam up til it burbled up and into the boats.

While night falls quickly here, it doesn't go quietly. For hours, lightning flickered and flashed over the northern bank, a polite reminder that we were guests of the rainy season. A ruder reminder arrived late the next afternoon, when the river led us directly into the maw of a wild storm that made a mockery of the tarp shelter we had optimistically erected. Deciding I could get no wetter, I dove into the river to help secure the tarps, finding it warm and swift flowing. I opened my eyes under water. I could see my hands before me, pulling me through rich tannin red light, as if I were weightless in prehistoric amber.

11 November 2005 (almost forgot to remember it was Remembrance Day).

A graveyard of rusty skeletal barges greets you on approach, an equally murdered crane also. A few walls remain to indicate what was once a building, perhaps a church. Nevertheless, Basankuso is the last pretence of urban civilisation for the rest of the river and we are obliged to acknowledge it by registering. Its 6.30 in the morning, mist is lifting, people on the riverbank wear jackets against the cool. From nowhere, a multitude of children materialise to gawp at the white people. A small fleet of dugout pirogues are parked diagonally nearby and women and children are washing their clothes and themselves in the shallows. I can hear singing coming from beneath a nearby tree.

A pair of planks over a muddy oily ditch leads up to a dusty clearing that functions as a marketplace. Indifferent looking women sit behind benches selling the same things- soap, washing powder, sacks of charcoal, onions, tomatoes, green and red peppers, prepaid telephone cards. A few ducks waddle around. In a flash, the fickle children abandon the whiteys and rush to the marketplace because the local army reserve seems to be going through their paces. In groups of about 30 they sweep down from the forest behind the town, through the marketplace, into the barracks and then back again.

Some are wearing army boots, others gumboots. All wear khaki somewhere but otherwise it is a mix of fake English soccer league chic and whatever else is eyecatching at hand. One muscular chap was wearing a fetching purple crop top to go with his camouflage pants. Each group shuffles/marches/jogs/jives to their own chant and are reinforced by their own witchdoctors, bedecked in radiating reed headpieces and skirts. One woman in shorts and gumboots strikes her own blow for sexual equality, joining the procession and refusing to be chased away. It is more dance and display than discipline, with much laughter, and they are gone as quickly as they appeared.

A graveyard of rusty skeletal barges greets you on approach, an equally murdered crane also. A few walls remain to indicate what was once a building, perhaps a church. Nevertheless, Basankuso is the last pretence of urban civilisation for the rest of the river and we are obliged to acknowledge it by registering. Its 6.30 in the morning, mist is lifting, people on the riverbank wear jackets against the cool. From nowhere, a multitude of children materialise to gawp at the white people. A small fleet of dugout pirogues are parked diagonally nearby and women and children are washing their clothes and themselves in the shallows. I can hear singing coming from beneath a nearby tree.

A pair of planks over a muddy oily ditch leads up to a dusty clearing that functions as a marketplace. Indifferent looking women sit behind benches selling the same things- soap, washing powder, sacks of charcoal, onions, tomatoes, green and red peppers, prepaid telephone cards. A few ducks waddle around. In a flash, the fickle children abandon the whiteys and rush to the marketplace because the local army reserve seems to be going through their paces. In groups of about 30 they sweep down from the forest behind the town, through the marketplace, into the barracks and then back again.

Some are wearing army boots, others gumboots. All wear khaki somewhere but otherwise it is a mix of fake English soccer league chic and whatever else is eyecatching at hand. One muscular chap was wearing a fetching purple crop top to go with his camouflage pants. Each group shuffles/marches/jogs/jives to their own chant and are reinforced by their own witchdoctors, bedecked in radiating reed headpieces and skirts. One woman in shorts and gumboots strikes her own blow for sexual equality, joining the procession and refusing to be chased away. It is more dance and display than discipline, with much laughter, and they are gone as quickly as they appeared.

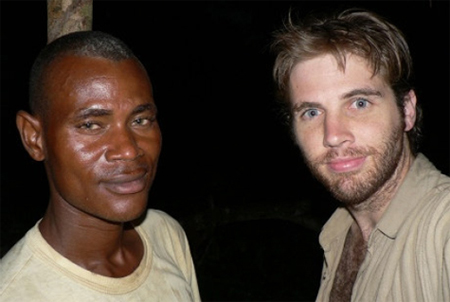

Myself & Paul - (Photos by martin Bendeler)

It was only a matter of time before I had to dive into the river with a crocodile. We asked a boatman if he had any fish to sell and he was most pleased to offer us a live trussed-up crocodile for $5 (Arne, who was once curator for reptiles for the Copenhagen zoo had it pegged for a dwarf crocodile (osteolaemis tetraspis), a CITES listed endangered species. Paul wanted to buy it to free it.). So pleased, in fact, that he tried to dock with us and, in so doing, capsized his own boat. He stood aghast on our prow as his pirogue filled with water and immediately turned to us for compensation.

I had only just woken up and was lying in my boxers on my mattress, but seeing this man's livelihood sinking downstream, I just jumped in after it. As I got closer, I remembered his canoe had a little grumpy crocodile in it, but by then it was too late. At any rate, the croc had his own problems, being tied up in a rapidly sinking dugout canoe. Anyway, I got to the canoe and kept it afloat, the boatman eventually joined me, we saved the croc and a basket of wriggly catfish, Charles reversed the boat and picked us up and all should have been well. But the boatman, adjusting his dripping ragged trousers around a waist that I could probably have encompassed completely with two fingers and was all sixpack and no stomach, complained bitterly that his hurricane lantern had gone down with the ship along with the rest of his very valuable catch and who was going to pay for it all. We bought his crocodile and his fish, shrugged our shoulders for the rest and sent him on his way. We then mugged for the cameras a little before releasing the critter in some reeds some distance upstream.

Sun 13th November 2005

Major towns ceased after Basankuso, though an unfriendly white man in an expensive speedboat was an indication we were near the missionary town of Maringa , eponymous with the river we were on. That was until we came across the illegal logging town of Bualu. Michael had been here 6 months ago when it was one shack.

Now it was a Congo Future company town of 500 people adjoining a modern lumber yard bursting with logs, bulldozers, lorries, warehouses and fuel tanks.

We pulled in to the river bank, ostensibly to buy fish and register. The usual gaggle of children and villagers gathered to be entertained by the sight of Paul in his mou mou.

Two guys with uniforms and guns were also there. One with a bit of grey and class, the other looked 16 and liked to do Rambo poses with his AK47. They readily agreed to let us walk around and take photos and footage as long as they could their mugs in the picture. We crossed the length of the village, gathering an entourage as we went, until we reached the wall of the lumber yard. I was filming as much as I could but soon word came that I had to dtop as it was private property. I did my best to keep spirits high amongst the crowd as final "paperwork" and shopping was attended to, anxious that they not get sullen and demand what the hell we were doing and money.

In the end we pulled out safely and once on the river, Michael did a piece to camera on the spread of illegal logging, of the incursions it made into bonobo habitat, and of the demand it generated for bushmeat. Children in the village were waving goodbye to us, while workmen in the lumber yard shook their fists.

At night, tarp down, reclining on my mattress, engine humming, the feeling of surging stable motion through the elements, I imagined I was flying Business Class 747 to Bonoboland....until I saw the million puncture wounds around my ankles where local critters have gone to town. The Chinese say the nerves in your feet link directly to all sorts of other places in your body, so I sometimes wonder what effect this will have elsewhere...

Major towns ceased after Basankuso, though an unfriendly white man in an expensive speedboat was an indication we were near the missionary town of Maringa , eponymous with the river we were on. That was until we came across the illegal logging town of Bualu. Michael had been here 6 months ago when it was one shack.

Now it was a Congo Future company town of 500 people adjoining a modern lumber yard bursting with logs, bulldozers, lorries, warehouses and fuel tanks.

We pulled in to the river bank, ostensibly to buy fish and register. The usual gaggle of children and villagers gathered to be entertained by the sight of Paul in his mou mou.

Two guys with uniforms and guns were also there. One with a bit of grey and class, the other looked 16 and liked to do Rambo poses with his AK47. They readily agreed to let us walk around and take photos and footage as long as they could their mugs in the picture. We crossed the length of the village, gathering an entourage as we went, until we reached the wall of the lumber yard. I was filming as much as I could but soon word came that I had to dtop as it was private property. I did my best to keep spirits high amongst the crowd as final "paperwork" and shopping was attended to, anxious that they not get sullen and demand what the hell we were doing and money.

In the end we pulled out safely and once on the river, Michael did a piece to camera on the spread of illegal logging, of the incursions it made into bonobo habitat, and of the demand it generated for bushmeat. Children in the village were waving goodbye to us, while workmen in the lumber yard shook their fists.

At night, tarp down, reclining on my mattress, engine humming, the feeling of surging stable motion through the elements, I imagined I was flying Business Class 747 to Bonoboland....until I saw the million puncture wounds around my ankles where local critters have gone to town. The Chinese say the nerves in your feet link directly to all sorts of other places in your body, so I sometimes wonder what effect this will have elsewhere...

The river is so high now, it is almost like floating at a bonobo's-eye view of the world, level with the lower canopy. We are not floating in a river, we are floating in a forest.

Mon 14 November 2007

Another storm in the night, but we were quickly at battle stations, fastening down the tarp and pulling in to a sheltered reedy bank. Wonderful thunder detonating across the sky, God’s crazy timpani solo, and I peaked under the tarp to see the strobe-lit rainy river.

We are still passing the occasional family compound of huts, the occasional pirogue, but now there are many more butterflies and birds - hornbills, herons, eagles. So very beautiful but so very little stopping it from being pulped....

More lumber dumps.

Butterflies- blue, green black swallowtails dive in flirtatious pairs, white ones flutter over the surface, taking occasional little kissing dips.

The sharpness of the afternoon, after-storm light, mist exhaling from the forest,

reflected sunset gold radiating from the gentle wake.

Another storm in the night, but we were quickly at battle stations, fastening down the tarp and pulling in to a sheltered reedy bank. Wonderful thunder detonating across the sky, God’s crazy timpani solo, and I peaked under the tarp to see the strobe-lit rainy river.

We are still passing the occasional family compound of huts, the occasional pirogue, but now there are many more butterflies and birds - hornbills, herons, eagles. So very beautiful but so very little stopping it from being pulped....

More lumber dumps.

Butterflies- blue, green black swallowtails dive in flirtatious pairs, white ones flutter over the surface, taking occasional little kissing dips.

The sharpness of the afternoon, after-storm light, mist exhaling from the forest,

reflected sunset gold radiating from the gentle wake.

Tue 15 Novemeber 2007

Still on the river. Charles' title as "Best Boatman on the Congo" could be revoked if it turns out it was him, and not his helper, who was at the till last night when we twice ran into overhanging branches in the space of 10 mins. Paul's tummy took the force of the first blow and it managed to knock over the hot coals in the stove (threatening to set the tarp and the boat on fire), as well as Michael and Arne (who was lucky to find his glasses again). Apart from a few scratches, everybody was OK and we calmed our nerves the way humans do (with some whiskey and honeyloaf) and not how bonobos do (with genital fondling and rump rubbing). This far upriver, it becomes increasingly

narrow and I suspect that the drivers are pushing it a bit harder at night than they otherwise would have in order to make up for lost time. The combination did not work out so well last night...

Charles (aka LeBlanc)- “Best Boatman on the Congo

(Photo- Martin Bendeler)

Still, I realised later we dodged a bullet. Worst case scenario would have seen us with a seriously wounded journalist, a capsized and incinerated boat, and us treading water in a river in the middle of Africa , 1000 miles from help. This blissful cocoon of comfort and ease is most fragile.

Little Violette contents herself with singing songs and playing with her dismembered Barbie, trying hard to give barbie an afro, though it looks more troll doll chic.

(Photo- Martin Bendeler)

Still, I realised later we dodged a bullet. Worst case scenario would have seen us with a seriously wounded journalist, a capsized and incinerated boat, and us treading water in a river in the middle of Africa , 1000 miles from help. This blissful cocoon of comfort and ease is most fragile.

Little Violette contents herself with singing songs and playing with her dismembered Barbie, trying hard to give barbie an afro, though it looks more troll doll chic.

This endless lazy hassle/responsibility-free (no calls, no news, no work) journey up a breathtakingly beautiful river has a surreal Huckleberry Finn aspect to it, occasionally tinged by the sad thought that it may all be pulped before my future children get a chance to see it.

The river is probably only 30m wide now, it’s midday and it flows quickly in shiny ripples and whorls. Tiny mites, only visible in the direct light, somehow swarm and surf upstream, buzzed by iridescent butterflies and birds. I'm resigned to never arriving and living forever in this beautiful limbo. Nina is drying our washed clothes on the tarp roof. Guys are sitting on empty barrels in the back. Paul is sleeping. Arne and Michael sit in quiet reflection in the front. I am on my bed, reading Emergency Sex- a UN whistleblower book.

Charles slowed the boat so Michael can jump in and take a dump, introducing to the African habitat the exotic American shitfish. The vastest, most beautiful toilet in the world. I am getting close to a place I have only read about- it’s a pilgrimage to a place that is pristine and holy. I am quietened and quickened. Few places in the world are this remote and beautiful. The bonobos truly live in Eden . Somewhere, something sweet is blooming. I can breathe it. It intoxicates. I'm sure I have dreamed of somewhere like this before- of a land of only trees and water- where I could move and breathe freely in both and was very happy. However my dreamland also hand big rocks in the river that I could skip across....

Charles slowed the boat so Michael can jump in and take a dump, introducing to the African habitat the exotic American shitfish. The vastest, most beautiful toilet in the world. I am getting close to a place I have only read about- it’s a pilgrimage to a place that is pristine and holy. I am quietened and quickened. Few places in the world are this remote and beautiful. The bonobos truly live in Eden . Somewhere, something sweet is blooming. I can breathe it. It intoxicates. I'm sure I have dreamed of somewhere like this before- of a land of only trees and water- where I could move and breathe freely in both and was very happy. However my dreamland also hand big rocks in the river that I could skip across....

Wednesday 16 November 2005

Have finally arrived in Kokolopori.

Couldn't quite believe it when we finally arrived at our final mooring point at dawn. The boat could not possibly go any further as the river finally narrowed to almost the dimensions of a doorway. There a softly sloping grassy bank waited for us, as well as some Kokolopori villagers, whose faces lit up to see Michael, Bienvenu, Charles and our hitchhikers. We quickly began unloading and soon more and more villagers appeared, smiling with hands outstretched, everybody wanting to shake hands, as if our presence to them was as otherworldly and welcome as that of the bonobos for me. A teenager, Keizei, took my bags and we headed off. Along the path we found villagers pouring down to get the paid work of carrying our goods.

The rainforest quickly closed in around us, the path barely discernable in the dense undergrowth, and it quickly lived up to its name when rain began to crash down. Various jungle smellsonions, honeysuckle, rotting fruit, potpourri fragrances. I kept up with the speedy lead group of porters as a bit of a macho thing, which was actually quite shallow, given they were half my age, height and weight and carrying twice my load. We passed through primary and secondary forest, fording streams and climbing trails that had become rivulets of muddy, puddly rainwater. We kept going and going and I realised I hadn't had any breakfast or water and looked forward to the feed that awaited me on arrival (also my stash of skittles in my pocket).

Then looked again at the porters, one boy grimacing under the weight of a suitcase on his head, and thought that they probably hadn't eaten either and probably no feast awaited them. I then recalled how the vast majority of the three million killed in the still recent war died from starvation and disease. Also thought of all the boatpeople and villagers I had passed who replied

to my waves by rubbing their tummies and making begging gestures. I called a halt and shared my water and Skittles (in the end, I got none!) then continued on. After a total 1.5 hr hike, I finally arrived at the village road. We had to pass through a number of villages and everyone waved and smiled in welcome, hordes of children spilled out to follow (squealing happily, "MONDELE! (Whitey)!" to which I replied with "MOINDO MOKE" (little blackey)). The houses were mudbrick with thatched roofs, scorched black due to no chimney. 19,000 people live here, children having babies, and the population pressure on bonobos must be intense.

Was taken to an area specifically prepared for visitors- A mudbrick compound of twelve rooms, two large shaded meeting areas in the middle, toilet, washing area and electric generator out the back. Surrounded by cassava groves (disease resistant, another BCI project) and forest. This was actually established with USD$3000 of seed funding from Australian GRASP (Great Ape Survival Project). GRASP perhaps naively expected the Aussie government to chip in $60k, but I have it on the very best authority that the Aussie government wouldn't care about a bonobo from Africa even if it arrived in a rickety boat without a proper visa in an Abu-Bakr Bashir t-shirt,

spouting Wahabbi doctrine.

We spent the rest of the day settling in to our comfortable but spartan huts, being welcomed by various worthies. In the afternoon, the Kokolopori Women's Association came dancing and singing through the gates- I think I could understand some of the Lingala lyrics- "we have joy, big joy, you have come, welcome". Many people here wear BCI t-shirts that read "Salisa bonono mpo na bonobo salisa yo"- “Help the bonobo so that the bonobo can help you”. They are very dedicated to bonobo protection and they also understand this brings much needed hard cash.

Have finally arrived in Kokolopori.

Couldn't quite believe it when we finally arrived at our final mooring point at dawn. The boat could not possibly go any further as the river finally narrowed to almost the dimensions of a doorway. There a softly sloping grassy bank waited for us, as well as some Kokolopori villagers, whose faces lit up to see Michael, Bienvenu, Charles and our hitchhikers. We quickly began unloading and soon more and more villagers appeared, smiling with hands outstretched, everybody wanting to shake hands, as if our presence to them was as otherworldly and welcome as that of the bonobos for me. A teenager, Keizei, took my bags and we headed off. Along the path we found villagers pouring down to get the paid work of carrying our goods.

The rainforest quickly closed in around us, the path barely discernable in the dense undergrowth, and it quickly lived up to its name when rain began to crash down. Various jungle smellsonions, honeysuckle, rotting fruit, potpourri fragrances. I kept up with the speedy lead group of porters as a bit of a macho thing, which was actually quite shallow, given they were half my age, height and weight and carrying twice my load. We passed through primary and secondary forest, fording streams and climbing trails that had become rivulets of muddy, puddly rainwater. We kept going and going and I realised I hadn't had any breakfast or water and looked forward to the feed that awaited me on arrival (also my stash of skittles in my pocket).

Then looked again at the porters, one boy grimacing under the weight of a suitcase on his head, and thought that they probably hadn't eaten either and probably no feast awaited them. I then recalled how the vast majority of the three million killed in the still recent war died from starvation and disease. Also thought of all the boatpeople and villagers I had passed who replied

to my waves by rubbing their tummies and making begging gestures. I called a halt and shared my water and Skittles (in the end, I got none!) then continued on. After a total 1.5 hr hike, I finally arrived at the village road. We had to pass through a number of villages and everyone waved and smiled in welcome, hordes of children spilled out to follow (squealing happily, "MONDELE! (Whitey)!" to which I replied with "MOINDO MOKE" (little blackey)). The houses were mudbrick with thatched roofs, scorched black due to no chimney. 19,000 people live here, children having babies, and the population pressure on bonobos must be intense.

Was taken to an area specifically prepared for visitors- A mudbrick compound of twelve rooms, two large shaded meeting areas in the middle, toilet, washing area and electric generator out the back. Surrounded by cassava groves (disease resistant, another BCI project) and forest. This was actually established with USD$3000 of seed funding from Australian GRASP (Great Ape Survival Project). GRASP perhaps naively expected the Aussie government to chip in $60k, but I have it on the very best authority that the Aussie government wouldn't care about a bonobo from Africa even if it arrived in a rickety boat without a proper visa in an Abu-Bakr Bashir t-shirt,

spouting Wahabbi doctrine.

We spent the rest of the day settling in to our comfortable but spartan huts, being welcomed by various worthies. In the afternoon, the Kokolopori Women's Association came dancing and singing through the gates- I think I could understand some of the Lingala lyrics- "we have joy, big joy, you have come, welcome". Many people here wear BCI t-shirts that read "Salisa bonono mpo na bonobo salisa yo"- “Help the bonobo so that the bonobo can help you”. They are very dedicated to bonobo protection and they also understand this brings much needed hard cash.

Hordes of children sneak into the compound to stare at the foreigners. Occasionally an elder shoos them away with a stick and they leave with maximum impudence, returning as soon as he turns his back.

I didn’t do it!---albino baby (Photos- Martin Bendeler)

I didn’t do it!---albino baby (Photos- Martin Bendeler)

Thursday 17 November 2005

A more substantial welcome ceremony today. First another dance from the Kokolopori Women's Association, led by a proud matron who called down the

blessings while the others chanted, clapped and swayed. About 20 women, the youngest about 18, the eldest completely indeterminate, and she would touchingly wipe the brow of the lead singer as she sung in her trance.

A more substantial welcome ceremony today. First another dance from the Kokolopori Women's Association, led by a proud matron who called down the

blessings while the others chanted, clapped and swayed. About 20 women, the youngest about 18, the eldest completely indeterminate, and she would touchingly wipe the brow of the lead singer as she sung in her trance.

(Photo- Martin Bendeler)

The women were displaced by an army of schoolchildren that had amassed at the compound gates. Thousands coming in class by class, singing. BCI had brought a shipment of donated school supplies from the States and they were to be presented by the president of their main NGO partner here, Chief Albert Lokasola.

At one point there was almost a disastrous stampede over Bic pens before order was reestablished. Children also pleased for opportunity to gawp at white people. One boy had a t-shirt that I could have sworn had written on it, "honkeys steal my underwear at night". Later, on closer inspection, I saw it was "monkeys", not "honkeys" but I still prefer the former interpretation as a playful, post-modern critique of neocolonialism....

Honkeys steal my underwear at night- (Photo- Martin Bendeler)

Four men entered the clearing with drums and got down to business, and all the other men gathered around in a funky, shuffling circle. Some elders had prime position.

One haughty looking old fellow with a sour trout pout and a dead chicken on his head. Another elder in a tattered Western suit, sandals, and a shiny brass medallion of King Leopold of Belgium hanging proudly around his neck, a sad enduring reminder of how cheaply and easily that old tyrant bought and raped this country. The bafande, the shaman, was there, dignified in nothing but a loincloth and a crown of hornbills.

(Photo- Martin Bendeler)

We spoke with the shaman afterwards. He told of how a village ancestor was lost in the forest, stuck up a tree, and a bonobo came to his aid. At that point, Leonard, the head tracker came by to say that if we wanted to see the bonobos before they settled in for the night, then we'd better get cracking.

We spoke with the shaman afterwards. He told of how a village ancestor was lost in the forest, stuck up a tree, and a bonobo came to his aid. At that point, Leonard, the head tracker came by to say that if we wanted to see the bonobos before they settled in for the night, then we'd better get cracking.

Paul got a lift to the start of the forest trail, about 5kms away, on Albert's motorbike while I set off on foot with the trackers. Quickly had my typical pied piper entourage of children in my wake, walking along a sunny green trail. We turned off at the last village, where forest trail led through manioc fields into light secondary forest. The frontier of the primary forest was guarded by a river of fire ants, who waited til they had crawled up your trousers, down your socks and into your shirt before all stinging on invisible, inaudible cue. The bonobos have formidable guardians. The HaliHali group of about 20 bonobos lived here. They are semi-habituated to humans, though if you are particularly lucky they will throw dung at you in displeasure, though I would rather receive dung from a bonobo than holy water from a priest...at least a bonobo is honest about his lecherous ways. Trackers had followed the group since dawn but their trail would have taken us into a swamp where we could miss them if they backtracked up the ridge to set up their night nests. So we paused for awhile, Paul on his fold-up safari chair, while the trackers fanned out to get a more immediate bearing. After about 20 minutes a tracker boy called out to say that the bonobos were ready and waiting for us. Crashing indecorously through the forest, we found Leonard pointing to the sky. At first, I couldn't see anything but more forest until…

Way up high, at least 60m up, a bonobo swung from a leafless branch over to a nearby tree to join his friends, who I could now see nestled in crooks, peering from trunks, and dangling from branches. Tapping his notebook, Leonard told us that he had observations to make and that his team would look after us from here on in. With that, we aligned ourselves with the movements of the bonobos, excitedly scrambling blindly over vines and logs with heads craned up in fixed awe. At one point, near a collection of old night nests, I counted eight bonobos, making the canopy sway and shake with their acrobatics. The males appeared much more robust than I had been led to expect. Little wiry infants scaled branches with that fearless clumsy happy tummyout insouciant way toddlers have of moving. At one point I heard something crashing with a heavy thud through the canopy to the forest floor and I immediately thought of the Japanese proverb "saru mo ki kara ochiru- even monkeys fall from trees" and

needlessly worried for the bonobos' welfare. As it turns out, the bonobos leave a lot more collateral damage in their wake than the nearby skinny monkeys with whom they share their great heights. I was initially worried a bonobo might shit on me, but realised it was dislodged branches and logs I should be worried about. We followed them awhile longer, as they effortlessly Spider-Manned their way through the canopy, gradually descending lower and lower. At one point I glimpsed a streak of black through a grove, all muscle and motion.

Way up high, at least 60m up, a bonobo swung from a leafless branch over to a nearby tree to join his friends, who I could now see nestled in crooks, peering from trunks, and dangling from branches. Tapping his notebook, Leonard told us that he had observations to make and that his team would look after us from here on in. With that, we aligned ourselves with the movements of the bonobos, excitedly scrambling blindly over vines and logs with heads craned up in fixed awe. At one point, near a collection of old night nests, I counted eight bonobos, making the canopy sway and shake with their acrobatics. The males appeared much more robust than I had been led to expect. Little wiry infants scaled branches with that fearless clumsy happy tummyout insouciant way toddlers have of moving. At one point I heard something crashing with a heavy thud through the canopy to the forest floor and I immediately thought of the Japanese proverb "saru mo ki kara ochiru- even monkeys fall from trees" and

needlessly worried for the bonobos' welfare. As it turns out, the bonobos leave a lot more collateral damage in their wake than the nearby skinny monkeys with whom they share their great heights. I was initially worried a bonobo might shit on me, but realised it was dislodged branches and logs I should be worried about. We followed them awhile longer, as they effortlessly Spider-Manned their way through the canopy, gradually descending lower and lower. At one point I glimpsed a streak of black through a grove, all muscle and motion.

(Photo- Martin Bendeler)

We followed in pursuit, Leonard always 20ms ahead, notebook in hand, gliding serenely and swiftly through the cluttered terrain as if God had appointed him an observer angel with divine laisser passer to discharge his single-minded duty. Leonard had been tracking and recording the bonobos for many years, even the dark war years, when he had no support nor shoes nor flashlight. He wants to publish his finding next year. The trackers followed the bonobo trail to an almost impenetrable thicket where we stopped to take stock of the time, the fading light, and the threatening thunder trembling through the jungle valley. Leonard suggested we call it a day and head back, leaving a few trackers to mark out the bonobo sleeping quarters for tomorrow's crew. BCI pays for the trackers to monitor and protect the bonobos every day, not just for when the rare white man wants to stumble through. Though we had only seen the bonobos briefly, it was a fine introduction to what I'm sure will be a beautiful relationship. Within 15 minutes we were back in the cassava fields on our way to the village. With perfect timing, darkness and rain fell as we arrived in the trackers’ hut, where we bought and distributed firewater in thanks and watched the lightning splash across the jungle hills. When the rain eased we hit the village-trail on the long walk back. The path was a pale hint through lush foilage in the moonless clouded darkness, with flickering faerie fireflies and lightning giving guidance. I set off carefree and infinitely pleased with my bonobo encounter but after awhile I became a little concerned that no matter how fast I powerwalked, I had the surreal sensation of walking on a treadmill with only fireflies as points of reference in the darkness, I began to think that we had overshot our mark and were marching swiftly ever further into the great jungle nothingness. I was freaking out a bit. Such is the night.

So pleased to finally see the electric lights of our compound that I did my own version of the happy-happy-joy song.

We followed in pursuit, Leonard always 20ms ahead, notebook in hand, gliding serenely and swiftly through the cluttered terrain as if God had appointed him an observer angel with divine laisser passer to discharge his single-minded duty. Leonard had been tracking and recording the bonobos for many years, even the dark war years, when he had no support nor shoes nor flashlight. He wants to publish his finding next year. The trackers followed the bonobo trail to an almost impenetrable thicket where we stopped to take stock of the time, the fading light, and the threatening thunder trembling through the jungle valley. Leonard suggested we call it a day and head back, leaving a few trackers to mark out the bonobo sleeping quarters for tomorrow's crew. BCI pays for the trackers to monitor and protect the bonobos every day, not just for when the rare white man wants to stumble through. Though we had only seen the bonobos briefly, it was a fine introduction to what I'm sure will be a beautiful relationship. Within 15 minutes we were back in the cassava fields on our way to the village. With perfect timing, darkness and rain fell as we arrived in the trackers’ hut, where we bought and distributed firewater in thanks and watched the lightning splash across the jungle hills. When the rain eased we hit the village-trail on the long walk back. The path was a pale hint through lush foilage in the moonless clouded darkness, with flickering faerie fireflies and lightning giving guidance. I set off carefree and infinitely pleased with my bonobo encounter but after awhile I became a little concerned that no matter how fast I powerwalked, I had the surreal sensation of walking on a treadmill with only fireflies as points of reference in the darkness, I began to think that we had overshot our mark and were marching swiftly ever further into the great jungle nothingness. I was freaking out a bit. Such is the night.

So pleased to finally see the electric lights of our compound that I did my own version of the happy-happy-joy song.

Miss Nina (Photo- Martin Bendeler)

Wonderful forest food of pineapples, papaya, bananas, plantains, lemons, liquid wild honey that makes the local firewater palatable, hard-shelled bush oranges with juicy, sticky, sweet, grey, brain-shaped chunks. Freshly baked bread. A steady slaughter of goats, pigs, chickens and ducks that have us feeling increasingly bloated and guilty. If I hear one more baby goat plaintively cry its last, I am irrevocably converting to vegetarianism. I know now they call them kids because they cry like children.

Wonderful forest food of pineapples, papaya, bananas, plantains, lemons, liquid wild honey that makes the local firewater palatable, hard-shelled bush oranges with juicy, sticky, sweet, grey, brain-shaped chunks. Freshly baked bread. A steady slaughter of goats, pigs, chickens and ducks that have us feeling increasingly bloated and guilty. If I hear one more baby goat plaintively cry its last, I am irrevocably converting to vegetarianism. I know now they call them kids because they cry like children.

Friday 18 November 2005 - Treefrogging

I was in a dark African swamp and Michael had just seen the vine he was about to grab slither slowly towards him. "Arne, what should I do if I see a green mamba?".

"Run" said Arne, one of the world's premier herpetologists, with characteristic Danish dryness. I decided then and there that treefroggery was not for me.

Earlier in the village, Arne had asked me why I had agreed to join him in his treefrog quest. I stood before him in ridiculous nipple-high rubber pants and briefly wondered the same thing before answering with something as silly as my pants, "Well the Japanese say a wise man climbs Mt Fuji once, but only a fool climbs it twice...I should give it a chance." The path to the swamp was an hour long walk along a narrow ditch through the manioc fields and the thick secondary forest. Clear water trickled through the terraced root structure of the liliana and manioc trees. Waded about in the water with Michael, Arne and three local boys, torches drawn, ears pricked. Frog music was broadcasting from everywhere. Surely it shouldn't be too hard. I turned my torch off, sat on a log and tried to get a bearing on a blighter.

Usually they were having a rather repetitive conversation with a nearby prospective mate which in treefroggish probably went something like this-

Boy frog- rebbit -"how about it?"-

Girl frog- arebbit -"how about what?"-

Boy frog- rebbIT -"how about IT!”

Rinse and repeat. Always repeat.

I was in a dark African swamp and Michael had just seen the vine he was about to grab slither slowly towards him. "Arne, what should I do if I see a green mamba?".

"Run" said Arne, one of the world's premier herpetologists, with characteristic Danish dryness. I decided then and there that treefroggery was not for me.

Earlier in the village, Arne had asked me why I had agreed to join him in his treefrog quest. I stood before him in ridiculous nipple-high rubber pants and briefly wondered the same thing before answering with something as silly as my pants, "Well the Japanese say a wise man climbs Mt Fuji once, but only a fool climbs it twice...I should give it a chance." The path to the swamp was an hour long walk along a narrow ditch through the manioc fields and the thick secondary forest. Clear water trickled through the terraced root structure of the liliana and manioc trees. Waded about in the water with Michael, Arne and three local boys, torches drawn, ears pricked. Frog music was broadcasting from everywhere. Surely it shouldn't be too hard. I turned my torch off, sat on a log and tried to get a bearing on a blighter.

Usually they were having a rather repetitive conversation with a nearby prospective mate which in treefroggish probably went something like this-

Boy frog- rebbit -"how about it?"-

Girl frog- arebbit -"how about what?"-

Boy frog- rebbIT -"how about IT!”

Rinse and repeat. Always repeat.

Anyway, you had to concentrate on one and not be tempted to go after the other, even if your original target fell silent for awhile, otherwise you would certainly get neither.

I couldn't seem to find any that were in convenient grasping distance and had to thrust my head through vines and spiderwebs and ants and every other African insect drawn to my torchlight. So I beat a retreat back into the stream and tried again until I got tired of my solo efforts and went to see if I'd be more useful helping others. Arne was poised near a tall crop of bamboo and reeds. Despite being deaf, blind and arthritic, his awesome reputation and intimidating eyebrows alone were sufficient to have every tree frog in his vicinity realise the futility of its position and offer itself up. I dazzled one lucky victim ("hydrolus fantasticus", murmured Arne) sitting on a veiny leaf with my torchlight while Arne's experienced hand made the snatch, then the stuff, into the plastic bag. If the frog was a coat it would be reversible, one side vivid green, one side scarlet. Michael had another frog in his sights, high atop a thin bamboo reed. Arne grabbed a long stick, placed one end next to the frog and talked the frog into shuffling across. Game over.

I couldn't seem to find any that were in convenient grasping distance and had to thrust my head through vines and spiderwebs and ants and every other African insect drawn to my torchlight. So I beat a retreat back into the stream and tried again until I got tired of my solo efforts and went to see if I'd be more useful helping others. Arne was poised near a tall crop of bamboo and reeds. Despite being deaf, blind and arthritic, his awesome reputation and intimidating eyebrows alone were sufficient to have every tree frog in his vicinity realise the futility of its position and offer itself up. I dazzled one lucky victim ("hydrolus fantasticus", murmured Arne) sitting on a veiny leaf with my torchlight while Arne's experienced hand made the snatch, then the stuff, into the plastic bag. If the frog was a coat it would be reversible, one side vivid green, one side scarlet. Michael had another frog in his sights, high atop a thin bamboo reed. Arne grabbed a long stick, placed one end next to the frog and talked the frog into shuffling across. Game over.

Congo tree frog…perhaps hydrolus fantasticus…perhaps not…

(Photo- Michael Hurley)

As for me, the novelty of splashing and stumbling in the wet and the dark for damned elusive frogs quickly wore off. Arne and I came across a spider as wide as a plate, then Michael asked Arne if his moving green vine was a green mamba or a boomslang (the first insanely venomous and territorial, the second just insanely venomous) and I decided to abandon the swamp with its delights of treefrogs, snakes, spiders, fireants, malaria- and possibly ebola- carrying mosquitos. Michael and Arne had at least a couple of hours left in them yet but I grabbed a village boy, resolutely straightened my silly plastic pants and headed home. I asked my guide "nkombo na yo, nini?- what is your name?". He was about 11 in shorts, t-shirt and flipflops. "Charley", he squeaked. An appropriate name for a little boy, I thought. Then after a pause he clarified with the infinitely grander, "Charlemagne". Phew.

Arne and Michael came back some time later to find the compound lit by lanterns as the generator had died for the night. I was grateful it was too dark to really look Arne in the eye after so cowardly abandoning his beloved calling of treefroggery.

Sunday 20 November

Woke up at 6.30 after another lovely lullaby storm slumber. Albert arrived round 7 and I tooled around on his motorbike for a bit. Waited at the trailhead. Went into forest. Chilled while trackers fanned out ahead. Sly buggers came back with downcast faces only to switch on the smile with the good news that bonobos had been found.

Brief trek and found some motion in the canopy. A few bonobos had settles here for an afternoon siesta. I lay back against a tree directly under an infant and closed my eyes awhile in solidarity. We sat silently for about 20mins then the infant above us woke up. His first reaction was to through some shit down at us. He then gave a wakeup squeal and suddenly the whole area was hooting and squealing from all angles. I had no idea so many were napping with us. For a good while they frolicked in the canopy. I counted about nine. Took me awhile to get my new binoculars oriented on a particular bonobo, but once I did, it was like Imax- my whole field of vision was beautiful, graceful, dignified bonobo.

Woke up at 6.30 after another lovely lullaby storm slumber. Albert arrived round 7 and I tooled around on his motorbike for a bit. Waited at the trailhead. Went into forest. Chilled while trackers fanned out ahead. Sly buggers came back with downcast faces only to switch on the smile with the good news that bonobos had been found.

Brief trek and found some motion in the canopy. A few bonobos had settles here for an afternoon siesta. I lay back against a tree directly under an infant and closed my eyes awhile in solidarity. We sat silently for about 20mins then the infant above us woke up. His first reaction was to through some shit down at us. He then gave a wakeup squeal and suddenly the whole area was hooting and squealing from all angles. I had no idea so many were napping with us. For a good while they frolicked in the canopy. I counted about nine. Took me awhile to get my new binoculars oriented on a particular bonobo, but once I did, it was like Imax- my whole field of vision was beautiful, graceful, dignified bonobo.

(Photo- Martin Bendeler)

Sometimes they would just step off a 50m branch like a Wall St suicide, plunging down to a desired level then lazily put out a hand to grab a branch as if it had taken an express elevator down. Or they would bounce up and down on a protruding branch as if on a divingboard, to get extra spring for a launch to another tree. Other times they would slide fireman-style down a slender branchless tree trunk. With their hypersexual reputation in mind, I immediately thought of poledancing. Yet they projected dignified equanamity, confidence, charisma, authority and power. Sometimes they would calmly look directly at me and I wondered what they made of these metallic things sticking out from my eyes and my khaki plumage.

Sometimes they would just step off a 50m branch like a Wall St suicide, plunging down to a desired level then lazily put out a hand to grab a branch as if it had taken an express elevator down. Or they would bounce up and down on a protruding branch as if on a divingboard, to get extra spring for a launch to another tree. Other times they would slide fireman-style down a slender branchless tree trunk. With their hypersexual reputation in mind, I immediately thought of poledancing. Yet they projected dignified equanamity, confidence, charisma, authority and power. Sometimes they would calmly look directly at me and I wondered what they made of these metallic things sticking out from my eyes and my khaki plumage.

They didn't really interact with each other so much. Felt a bit perverted wishing that apes would have sex for my viewing pleasure. They quite rightly didn't give me the satisfaction. They moved as a dispersed group in a general direction and we followed from varying distances. Sometimes I would watch one relaxing in a crook of a tree, one leg gracefully stretching straight up, the other plucking some leaves to munch. Another time one male sat on a branch like a teenager, legs swinging under him, shoulders hunched, silhouetted as he contemplated the sunset. I was too busy watching someone else through my binoculars but Paul saw a female clamber down a tree about 10 metres away and gracefully skip by on two legs across a mossy fallen log. So excited following alongside the bonobos that I didn't notice the long afternoon shadows and shafts of cathedral light or my grumbling tummy or parched throat. Just as we were about to leave, a young adult male came halfway down a very close tree and regarded us, as if giving a parting favour by posing for a photograph.

Leonard led us back to our campsite. Ate rice, pineapple and beef jerky by campfire. Fireflies, stars through the canopy, phosphorescent leaves in the moonlight. Spoke with Paul until relatively late (i.e. 8.30) then entered my virgin tent. Trackers snored nearby under the stars on bamboo beds hastily hacked together by machete. They will wake at 3am to check on the bonobo nests then we will head out together to see how a bonobo greets the day...

Monday 21 November 2005

Fitful sleep. We had planned to have only three in the camp- myself, Paul and Leonard- and had 3 tents accordingly. Albert had said that three was enough to keep the leopards away but not too much as to scare the snoozing bonobos. But somewhere Leonard disappeared and was replaced by 10 trackers (who normally walk back to the village after work).

Five piled into Leonard’s tent like children at a slumber party.

Still, the trackers more than redeemed themselves in taking us to the bonobo nesting site in the morning twilight. Again, we reclined against a tree where slept a youngster.

He woke up, and, as boys are wont to do, had a morning piss, from very great heights. They were scattered across quite a wide area and through my binoculars I could see them quietly awake and stretch and enjoy a contemplative leaf breakfast in the golden morning light. Got up, got out of bed, dragged a comb across my head. As the day lightened, they abandoned their beds and grazed on branches and leaves. A female reclined at the end of branch that seemed too slight to support her, languidly masticating. After awhile another female approached, with an outstretched supplicating hand. On this narrow branch, 50m up, they somehow exchanged positions and then the first bonobo came back, almost as an afterthought, and they vigorously rubbed their genitals together for about half a minute before going back to their feeding. It was actually rather perfunctory, more a friendly morning greeting than lesbian sex inferno.

Fitful sleep. We had planned to have only three in the camp- myself, Paul and Leonard- and had 3 tents accordingly. Albert had said that three was enough to keep the leopards away but not too much as to scare the snoozing bonobos. But somewhere Leonard disappeared and was replaced by 10 trackers (who normally walk back to the village after work).

Five piled into Leonard’s tent like children at a slumber party.

Still, the trackers more than redeemed themselves in taking us to the bonobo nesting site in the morning twilight. Again, we reclined against a tree where slept a youngster.

He woke up, and, as boys are wont to do, had a morning piss, from very great heights. They were scattered across quite a wide area and through my binoculars I could see them quietly awake and stretch and enjoy a contemplative leaf breakfast in the golden morning light. Got up, got out of bed, dragged a comb across my head. As the day lightened, they abandoned their beds and grazed on branches and leaves. A female reclined at the end of branch that seemed too slight to support her, languidly masticating. After awhile another female approached, with an outstretched supplicating hand. On this narrow branch, 50m up, they somehow exchanged positions and then the first bonobo came back, almost as an afterthought, and they vigorously rubbed their genitals together for about half a minute before going back to their feeding. It was actually rather perfunctory, more a friendly morning greeting than lesbian sex inferno.

Bonobos not doing lesbian sex inferno (Photo- Martin Bendeler)

The bonobos began to head down towards the swamp to wash and forage for food, brachiating through the canopy. I was taken aback to look through my binoculars and see a bonobo make a complicated aerial maneuver around a heavily vegetated treetop. More so, because I didn't move my binoculars and saw another bonobo follow and perform the exact same sequence in the same place. It was as if they were following a well-traveled highway and they had come to a turnpike. A very high way, with a triple turn in the pike position. As they got closer to the swamp, they began to descend lower and lower, some performing the patented bonobo express elevator drop, others a shimmy. One female showed Michael Jackson parenting skills, plunging at least 10 metres to a lower branch with a baby clinging for dear life (or fun) to her belly. The swamp terrain became very difficult, with clinging, thorny vines, sinking leaf litter over mud and streams, crumbling logs. Paul thought it best to wait in clearer ground for the bonobos to leave the swamp. The trackers invited me to join them, so I plunged in, hoping to see the bonobos on the ground, where they could interact more.

The bonobos began to head down towards the swamp to wash and forage for food, brachiating through the canopy. I was taken aback to look through my binoculars and see a bonobo make a complicated aerial maneuver around a heavily vegetated treetop. More so, because I didn't move my binoculars and saw another bonobo follow and perform the exact same sequence in the same place. It was as if they were following a well-traveled highway and they had come to a turnpike. A very high way, with a triple turn in the pike position. As they got closer to the swamp, they began to descend lower and lower, some performing the patented bonobo express elevator drop, others a shimmy. One female showed Michael Jackson parenting skills, plunging at least 10 metres to a lower branch with a baby clinging for dear life (or fun) to her belly. The swamp terrain became very difficult, with clinging, thorny vines, sinking leaf litter over mud and streams, crumbling logs. Paul thought it best to wait in clearer ground for the bonobos to leave the swamp. The trackers invited me to join them, so I plunged in, hoping to see the bonobos on the ground, where they could interact more.

Felt honoured to follow Leonard's lead as he quietly, effortlessly, glided through the tangle, sans machete, following the bonobo signs- hair, fruit, dung, urine scent, distant calls. The bonobos were always just a little bit ahead. Until at one point I looked up from navigating a swampy section that was all roots, mud and leaf litter to see a bonobo climb down a tree 10 metres away, look at me in startlement, and vanish into the viney undergrowth.

All the bonobos and all the trackers (and friends) homed in on a particular clearing, the bonobos to siesta, the others to wait for them to wake up. The bonobos would greet each arriving group crashing through the canopy with hoots of happiness.

For a good long while we watched entranced.

Tuesday 22 November 2005

I heard a rising hubbub down the village path. Initially I thought maybe the peasants were massing with pitchforks and torches to lynch us on account of Arne's satanic frog rituals and Mephistolean eyebrows and beard. Turns out it was democracy on the move.

I heard a rising hubbub down the village path. Initially I thought maybe the peasants were massing with pitchforks and torches to lynch us on account of Arne's satanic frog rituals and Mephistolean eyebrows and beard. Turns out it was democracy on the move.

Democracy on the move (Photo- Martin Bendeler)

Voter registration. Computer database. Biometrics fingerprint and digital photograph. Dell laptop in protective foam casing. In a BCI community centre using BCI generator and UHF radio. The 4 person team had walked from Djolu, with porters and Two policemen. Long line. 3-5 per hour. 10,000 to register in this area alone.

Registration to continue well into December. A young man had set up a stall on a table selling combs, razorblades, antibiotic cream, 50 cent torches and small mirrors.

Democracy's camp follower. Some pigs wandered around. I think I saw some bonobos waiting patiently in line to register. They're very intelligent, you know.

Two CREF (Centre for Ecological and Forestry Research) researchers arrived by bike from Wamba. They do most of the legwork for the Japanese, who treat them quite poorly. The University of Kyoto team seem, not entirely unreasonably, more devoted to research than bonobo conservation, with its attendant community development imperatives. But hard to do research on dead bonobos….

More bonobo observations from Congolese field researchers-

The alpha male makes most of the major decisions- when to wake up and when to sleep, when to move on from feeding or napping, threat assessment and response, territorial defence etc. However, the alpha female, who may often be the mother of the alpha male (kind of a King and Queen Mother type of monarchy) and some of his allies, has a veto and noone will follow the alpha male if she doesn't. The alpha female is the only group member permitted to groom the alpha male. Bonobos will always fight if another group violated their territorial integrity, often inflicting deep wounds, but never killing, let alone the brutal mutilation characteristic of chimp conflicts. Group encounters between fractured groups (when one splits from another) are peaceful. There is never any serious violence within the group.

Leonard said that while he could not confirm the veto power of the female, the alpha male definitely made most of the decisions. Moreover, when the group moved, one male would always take the point while another would bring up the rear. He considered the current alpha, Raphael, was on his way out as he was getting older and had moved from the fore to the rear.

After Japanese ended provisioning, the bonobos ranging much further, sometimes more than 20kms in a day. Much harder to analyse group dynamics as most observations now are made of arboreal behaviour. Very hard to track on ground. The war reduced the size of their study group from 45 to 23.

The African researchers said that while provisioning continued, there was no research or even interest in the extent of bonobo range or their territory.

With provisioning or captivity, the closer proximity to each other leads to different outcomes than in the wild. For example- when an alpha chimp is about to completely go off his rocker over something, he will stand and sway for about 10 seconds, his eyes will glaze over and then heaven help whoever gets in his way. However, in captivity, there is often time for for females to quickly remove all possible weapons from near the alpha before he starts his rampage. In the wild, with wider foraging, this cannot happen.

Similarly, key aspects of bonobo behaviour may depend on the conditions in which their livelihood is obtained. It could well be that the complex shared responsibilities and checks and balances between the sexual leadership that prevails when open ranging for food is warped when food is centrally located. Perhaps almost a reverse of human history, where settled agriculture allowed powerful men to establish violent monopolies over land and by extension, food and women.

Strange to think of the bonobo alpha male, emasculated by Japanese provisioners. All his responsibilities- directing the troop, guarding the perimeter- made redundant by a sedentary lifestyle.

Half jokingly thought that it was not the end of provisioning that brought about moreviolently territorial behaviour but the contemporaneous outbreak of war. Maybe the bonobos were influenced by human behaviour to become more defensive and less trusting. Also thought that maybe the war may not have been the only reason for the reduction in Wamba bonobo numbers. Perhaps pre-war, the bonobos had been smart enough to migrate from other areas for the free Japanese food and then they returned to their traditional ranges after provisioning ceased….

Thursday 24 November 2005

Packed our bags and headed back to the boat, down the village path and then through the jungle. Probably about a 10km walk. Fortunately, we had half the village employed as porters. Normally you wouldn't think people would be tripping over themselves to carry heavy objects long distances, but cash is so scarce here that any opportunity is leapt upon. It is as if they are living in a permanent Great Depression. I felt guilty not carrying a single thing while children carried my stuff for probably less than 25 cents. But 25 cents was the only money they were likely to see for a very long time.

Arrived at the river around 3pm and settled in. We would sleep there, then leave at first light to get through the difficult upper reaches of the river.

I dived into the river and let the swift flow take me a short distance until I hooked my hand around a protruding branch. I just lay on my back like that in the cool water, with my head tilted back at the sky and my feet dragged forward by the current. Incipient storm clouds raced across the sky, jagged layers of gray, and high high up tiny birds darted and hunted and I wondered why insects would fly so high. Couldn't tell if the rushing noise in my head was my blood or the river but it cleared my thoughts while the river held me aloft in its embrace. Thought how wonderful this place was, how wonderful I felt, how I would be leaving but how I wanted to come back. Thought again of the bonobos. How they had regarded me impassively. How they had thrown sticks and howled at Paul today. How the African researchers had said there is a newfound awareness of bonobo territoriality. How I didn't go and see them when I had more opportunities to do so because of this sense of intrusion. Yet how I wanted to see them again and, moreover bring others to see them, if only to raise money and awareness to protect them. I understood now why hunter-gatherer cultures have rituals and ceremonies to placate and reconcile with the animals they depend upon. Lying in the river, I realised I needed the shaman's help and vowed to talk to him when I returned.

Friday 25 November 2007,

Packed our bags and headed back to the boat, down the village path and then through the jungle. Probably about a 10km walk. Fortunately, we had half the village employed as porters. Normally you wouldn't think people would be tripping over themselves to carry heavy objects long distances, but cash is so scarce here that any opportunity is leapt upon. It is as if they are living in a permanent Great Depression. I felt guilty not carrying a single thing while children carried my stuff for probably less than 25 cents. But 25 cents was the only money they were likely to see for a very long time.

Arrived at the river around 3pm and settled in. We would sleep there, then leave at first light to get through the difficult upper reaches of the river.

I dived into the river and let the swift flow take me a short distance until I hooked my hand around a protruding branch. I just lay on my back like that in the cool water, with my head tilted back at the sky and my feet dragged forward by the current. Incipient storm clouds raced across the sky, jagged layers of gray, and high high up tiny birds darted and hunted and I wondered why insects would fly so high. Couldn't tell if the rushing noise in my head was my blood or the river but it cleared my thoughts while the river held me aloft in its embrace. Thought how wonderful this place was, how wonderful I felt, how I would be leaving but how I wanted to come back. Thought again of the bonobos. How they had regarded me impassively. How they had thrown sticks and howled at Paul today. How the African researchers had said there is a newfound awareness of bonobo territoriality. How I didn't go and see them when I had more opportunities to do so because of this sense of intrusion. Yet how I wanted to see them again and, moreover bring others to see them, if only to raise money and awareness to protect them. I understood now why hunter-gatherer cultures have rituals and ceremonies to placate and reconcile with the animals they depend upon. Lying in the river, I realised I needed the shaman's help and vowed to talk to him when I returned.

Friday 25 November 2007,

Charles’ helpers untied the twined mooring vines and we set off. The river was racing, cluttered with trees fallen when the wet season rains weakened their root structures.

No river banks, just branches and mangroves and serrated reeds. Everyone could see the jutting branch but noone could do anything about it. Like an iceberg, the innocuous looking exposed branch had a substantial tree submerged beneath it. Like the Titanic, we had too much momentum to swerve away. It cleaved down the middle of the two boats, with much cracking, creaking and shaking, til eventually it had us snagged good and proper. Unlike the Titanic, that was the worst of it. Almost. The prow of the boat bumped into the riverside, waking up a hive of slumbering wasps, who were definitely not morning insects. They homed in like smart bombs on the exposed skin of our crew, who hopped about slapping and launching cloudy fusillades of insecticide spray that only seemed to drive the endless friends of the waspy dead into vengeful wrath. But Charles and his crew took it all in their stride and soon we were on our way again, the swift pace downriver in the morning light, a marked contrast to the painful crawl in the night when we arrived.

No river banks, just branches and mangroves and serrated reeds. Everyone could see the jutting branch but noone could do anything about it. Like an iceberg, the innocuous looking exposed branch had a substantial tree submerged beneath it. Like the Titanic, we had too much momentum to swerve away. It cleaved down the middle of the two boats, with much cracking, creaking and shaking, til eventually it had us snagged good and proper. Unlike the Titanic, that was the worst of it. Almost. The prow of the boat bumped into the riverside, waking up a hive of slumbering wasps, who were definitely not morning insects. They homed in like smart bombs on the exposed skin of our crew, who hopped about slapping and launching cloudy fusillades of insecticide spray that only seemed to drive the endless friends of the waspy dead into vengeful wrath. But Charles and his crew took it all in their stride and soon we were on our way again, the swift pace downriver in the morning light, a marked contrast to the painful crawl in the night when we arrived.

Good to be back on the river again. After mentally editing out the drone of the outboard motor, I am left blessed with swathes of soothing green around me, the rain of most of Africa distilled and gurgling and giggling below me, and the vast shifting sky of sun and clouds and mist and dawns and sunsets above me.

Like before, I lie back in my bed and take it all in. However, I am still haunted by bonobos, if that is the right word. Her eyes, looking back over her shoulder directly at me, still resonate in my mind. I don’t know what they are telling meacknowledgement? Puzzlement? Go away? Probably nothing in particular, but I still see them. I sometimes flatter myself to think she is probably in the canopy now, absentmindedly stripping a branch of leaves and trying to figure out my strange blue eyes. At any rate, I’ve got some issues to sort out. Apparently last night I screamed for about 3 seconds in my sleep. Don’t think I’ve ever done that before. Colobus monkeys tracked alongside us for awhile, slightly querulous-looking despite being garbed in the most resplendent of shaggy black and white coats. Chimps eat them. Starting to think bonobos might, too.

Like before, I lie back in my bed and take it all in. However, I am still haunted by bonobos, if that is the right word. Her eyes, looking back over her shoulder directly at me, still resonate in my mind. I don’t know what they are telling meacknowledgement? Puzzlement? Go away? Probably nothing in particular, but I still see them. I sometimes flatter myself to think she is probably in the canopy now, absentmindedly stripping a branch of leaves and trying to figure out my strange blue eyes. At any rate, I’ve got some issues to sort out. Apparently last night I screamed for about 3 seconds in my sleep. Don’t think I’ve ever done that before. Colobus monkeys tracked alongside us for awhile, slightly querulous-looking despite being garbed in the most resplendent of shaggy black and white coats. Chimps eat them. Starting to think bonobos might, too.

Iridescent kingfishers. Black Kites soaring river thermals.

The boat skids across the sunken treetops, shuddering as branches scrape along the hull.

We’ve got one less boat this time, and three less hitchhikers. Nina is on board again to cook, while Charles has his helpers- Meda and someone else. We are also taking Valentin. She is about 20 and heading to Kinshasa to study nursing. She already has a diploma in teaching. It’s good to promote further education in the village, especially among women. The specific development needs of women are so evident and compelling that I sometimes find myself sounding a bit like Stan in the Monty Python Life of Brian (“What is it with you and women, Stan?, “I want to be one. From now on, I want you all to call me Loretta….”). What is it with you and women, Martin?

Along the path to the river yesterday, many villagers came out to say goodbye. At one bend, I met four or five young men, 18 or 19. One said to me in Lingala that his name was also Martin and he shyly offered me an egg in expectant reciprocation, though I really had no place or use for an egg. His friend surprised me with English, albeit strained- “His name…Martin, too. He says you are brothers. He says please help him…because he has”, then the most heartbreaking pause, stutter and sigh, “...n-n-nnothing.”

It sums it all up, really, doesn’t it? I would start a stampede if I started handing out money so therefore carried none, but I definitely will do all I can to help these people, for their own sake, for my own sake and for the sake of the bonobos.

I don’t think I quite explained just how beautiful the bonobos are. They have a presence, a dignity, a gravitas, that you expect in gorillas. A powerful posture, eyes that are languid, intelligent and contemplatative. Hard to describe their face- placid? Stern? Open? Impassive? Most definitely striking, with dark smooth skin, expressive mouths, and a flop of characteristic middle-parted hair. There is no mistaking the regal bearing of Raphael and Suzie, the alpha male and female respectively, nor their powerful build and carriage. The bulk of one older feller’s mass had descended from his shoulders and chest to settle comfortably around his middle.

It sums it all up, really, doesn’t it? I would start a stampede if I started handing out money so therefore carried none, but I definitely will do all I can to help these people, for their own sake, for my own sake and for the sake of the bonobos.

I don’t think I quite explained just how beautiful the bonobos are. They have a presence, a dignity, a gravitas, that you expect in gorillas. A powerful posture, eyes that are languid, intelligent and contemplatative. Hard to describe their face- placid? Stern? Open? Impassive? Most definitely striking, with dark smooth skin, expressive mouths, and a flop of characteristic middle-parted hair. There is no mistaking the regal bearing of Raphael and Suzie, the alpha male and female respectively, nor their powerful build and carriage. The bulk of one older feller’s mass had descended from his shoulders and chest to settle comfortably around his middle.

Vivisectionists may coldly say they are not as heavy as chimpanzees, and they may have a reputation for affection, but nothing about them at all suggests effete weakness. They are big and broad and strong, muscle on muscle. Both the males and females project power and authority. These are not simpering sex apes. But they do have an unmistakable elegance. Their movements are deliberate. They unfurl their arms and legs, draping themselves over forest angles, and then you see the longest and most graceful hands- from finger to palm, as long as my forearm. If need be, they can hang effortlessly from their very fingertips. Their feet are mirrors of their hands and they lazily pluck shoots and leaves and fruit with them. They can make love hanging upside down by their feet, 50m above the ground. Need I say more?

Makes you ache that you cannot move with such freedom in an environment so wonderful. Makes you curse the poverty of your two-dimensional world.

They seem completely at home in the environment and, what’s more, they very clearly look like they know it.

Makes you ache that you cannot move with such freedom in an environment so wonderful. Makes you curse the poverty of your two-dimensional world.

They seem completely at home in the environment and, what’s more, they very clearly look like they know it.

Fishing camp- (Photo- Martin Bendeler)